Six years ago to this very minute (just after 9 in the morning) I was under the streets of New York, riding to work on the subway, lucky enough to get a seat so I could read without getting jostled. The book was Barry Miles' The Beat Hotel, an account of the subterranean literary figures Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs, Brion Gysin and Gregory Corso as they mixed it up in a rundown little Paris fleabag in the 50s and 60s. The passage I was reading dealt with a mysterious 11th Century figure named Hassan I'Sabbah, Grand Master of the Ismaili Hashishim sect, or Assassins, who indoctrinated and trained his legions in his hidden mountain stronghold of Alamut, Persia, and sent them forth to infiltrate Seljuk Turkish society and kill their political enemies. His invisibility and omnipresence fascinated Burroughs and Gysin; they adopted him as a symbol of occult subversion in their Cold War era, mass media conscious art. He became known to the Turks as "The Old Man of the Mountain," a terrifying bogeyman for grown men who feared waking to find his dagger in their pillows, dire warnings attached. That morning on the subway, I reflected on how historic figures eventually inherit the clothing of old archetypes. The latest Middle Eastern bugaboo came to mind, a rich Saudi hidden somewhere in the mountains training his own loyal, deluded legions to go forth and blow up embassies. I couldn't recall his name.

I think I was still struggling to remember when I got off at 23rd Street, emerged into the sunlight and stopped and stared, in the midst of a silent sidewalk crowd, at the sight of the burning Twin Towers; they were perfectly framed by the chasm of Fifth Avenue. I haven't forgotten his name since that day.

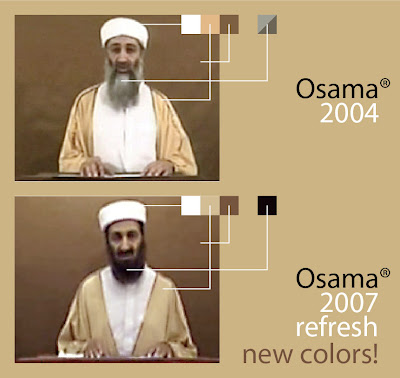

And now, six years on, OBL has receded and grown omnipresent. He seems to occupy a chamber of our minds, rather than a point in time and space. In his most recent video, he even appears to be growing younger, sporting a dense black beard. Here, the archetypes coalesce and blur. Bram Stoker's Dracula grew younger as he gorged on the blood of his victims, his hair turning black from a snowy white over the course of the novel; he was, interestingly enough, another incarnation of the Oriental Other, threatening Victorian Western stability. Of course, in the age of electronic and digital media, there's a more useful term for these enduring, stealthy archetypes who inhabit our dreams and nightmares. We call them brands. And apparently OBL and/or his handlers, whoever they may be, have a decent grasp of branding principles: keep the brand consistent and straightforward, a quick read in the saturated media environment. Use a select color palette. And refresh the brand every few years, whether it takes a leaner typeface, or a henna dye rinse. The Old Man must stay young. He doesn't even have to stay alive: Elvis and Marilyn, Kerouac and Ché Guevara, even Hitler are powerful brands today. All it takes is a responsive target audience.

This is one brand I'd like to relegate to the scrap heap. No Logo indeed.